Australia has had a less awful time with covid-19 than most of the world. The 80% of Australians who don’t live in Melbourne have been living mostly-normally for almost a year. Even Melburnians have done far better than the rest of the rich world as far as illness and deaths go. They’ve also done better than much of the rich world as far as lockdowns go, too, after enduring last winter/spring’s marathon.

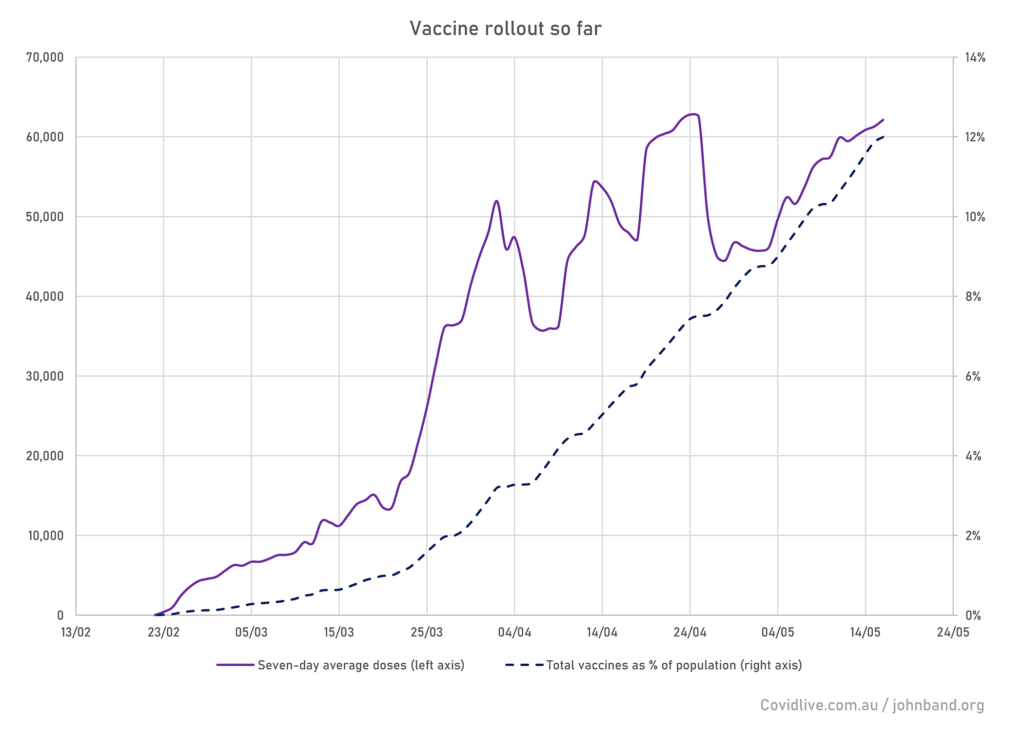

However, we’ve had an unimpressive covid-19 vaccine roll-out so far. The total number of vaccines administered up to the end of 15 May is equal to 12% of the population. This compares to 120% in Israel, 73% in the UK and USA, 36% in Germany, 19% in Hong Kong, 7% in Taiwan, and 6% in New Zealand:

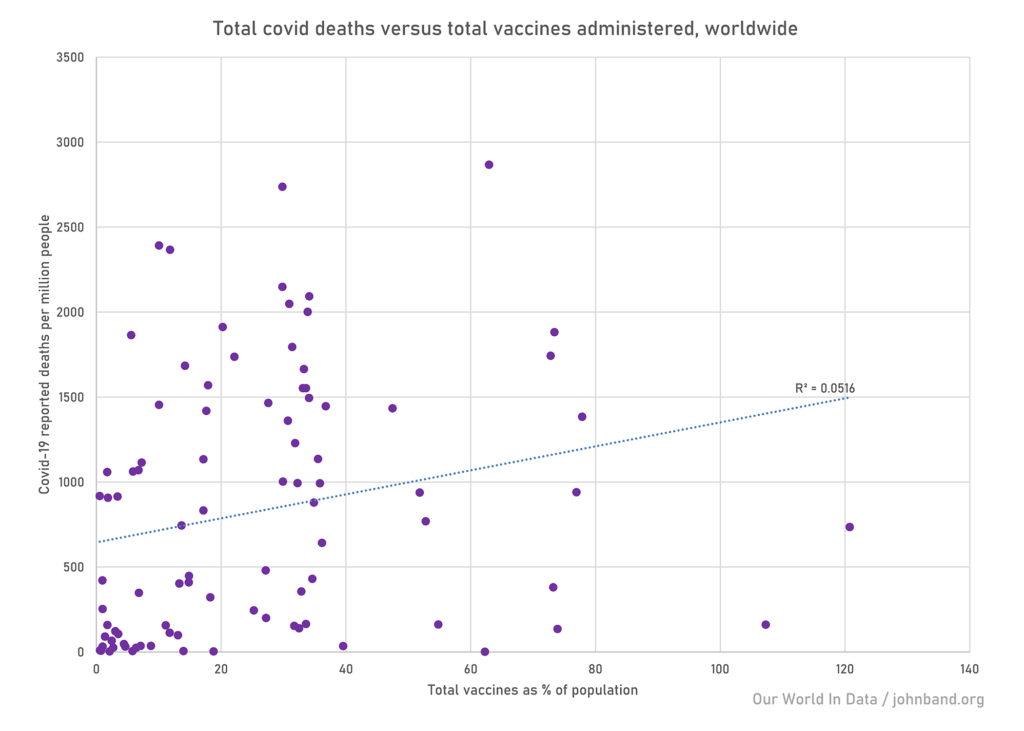

My inclusion of high-vax, high-death countries and low-vax, low-death countries in the previous paragraph wasn’t a coincidence. We aren’t alone in our lack of roll-out urgency. Here’s a scatter graph showing the world’s vaccine roll-out (doses per % of population) alongside covid deaths per million people. There’s a weak but visible positive correlation. People are more inclined to get jabbed (and governments more likely to arrange jabs) if the alternative looks like an unpleasant death than if unpleasant deaths are just a story on the world news.

Why do we need to hurry up vaccine roll-out anyway?

This matters because, although Australia has managed to give most people a relatively normal life, the cost has been substantial. International borders have been shut for over a year, with no clear re-opening time. Tens of thousands of Australians currently overseas are unable to get home; international tourism has been destroyed; the 30% of Australians who were born overseas are unable to see their families; and the migration program that’s driven Australia’s transformation from colonial backwater to diverse thriving nation has been almost completely frozen. Vaccination is the only way to escape from this stagnation – even if you (wrongly, but that’s a story for another day) assume the chances of breaching our bubble and experiencing another outbreak are negligible.

The Australian public consensus on vaccination is currently grimly negative. Our hopelessly incompetent Prime Minister overpromised, as he always does. Early stages were reliant on AstraZeneca delivering doses from European facilities which were subjected to export bans. Just as numbers started to improve, the (silly, but that’s a story for another day) global clotting panic over AstraZeneca meant that the only locally manufactured vaccine couldn’t be given to under-50s.

Since then, the AstraZeneca clotting story has been seized upon by anti-vaxxers, media sensationalists and partisan hacks as a way of driving vaccine hesitancy among over-50s, for whom it remains the recommended vaccine. So we’ve been suffering from both lack of supply and lack of demand. According to the Guardian, at current vaccination rates it would take 30 more months to give adults two vaccine doses.

This is all bleak stuff – but there’s good reason to think that the tide is turning.

The rolling average chart shows a much better vaccine story for May, with the seven-day average consistently rising. More Pfizer doses have arrived from overseas, and the major states have set up mass public vaccination hubs. These are currently scaling up to provide high-capacity doses to anyone who can get there. Here’s your correspondent at one last week:

So what do we do next?

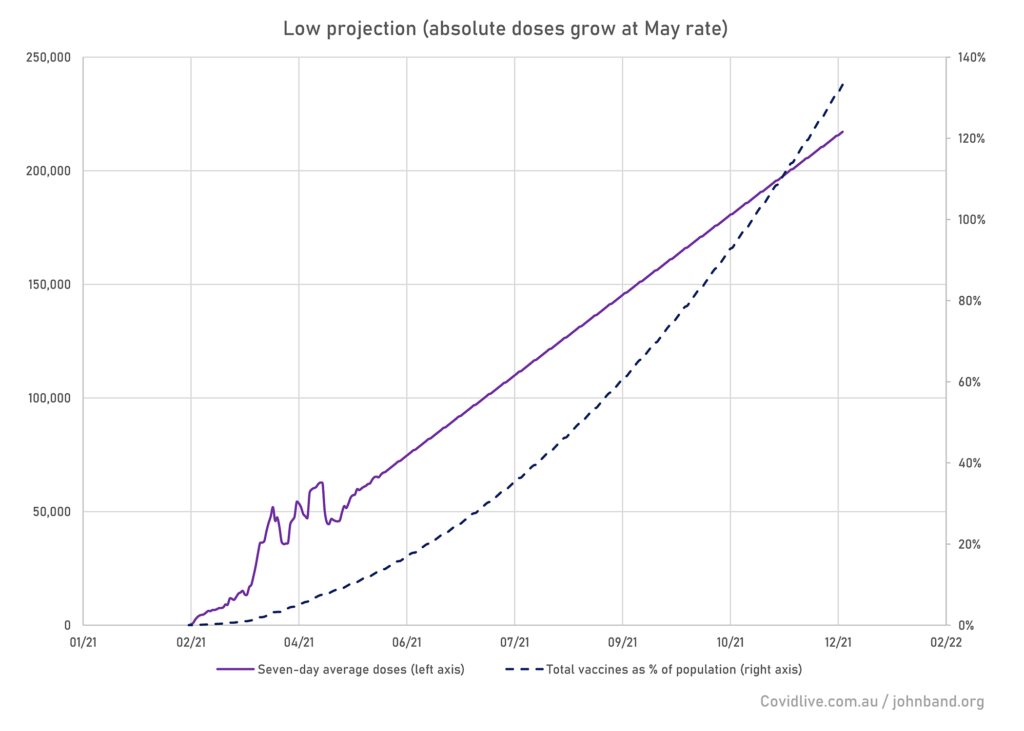

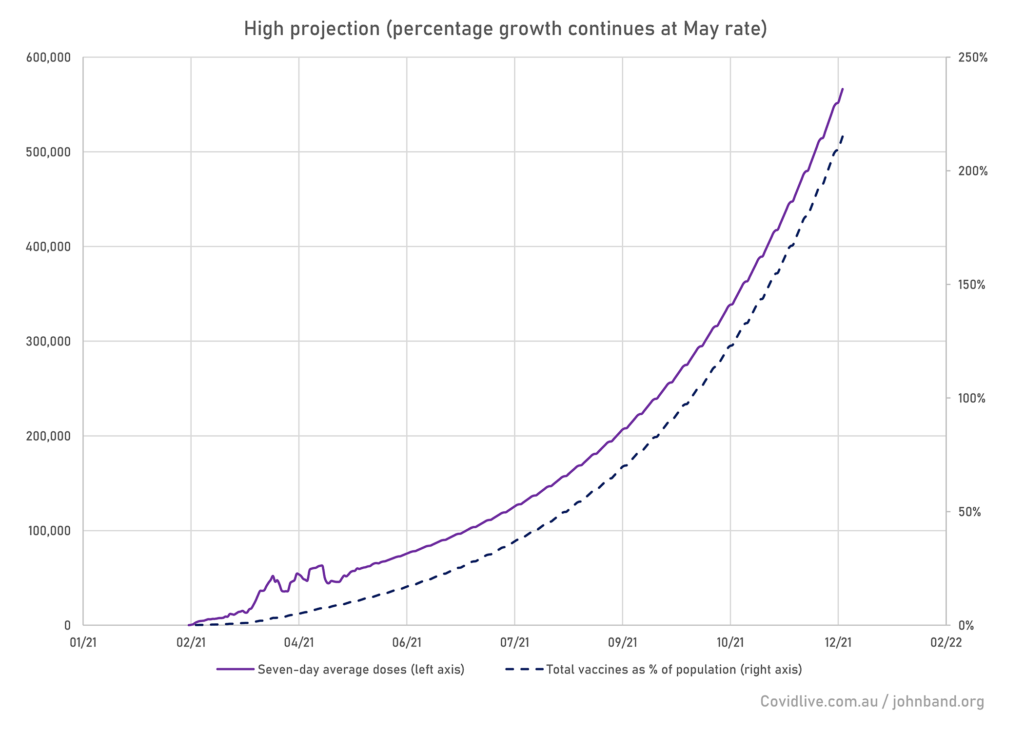

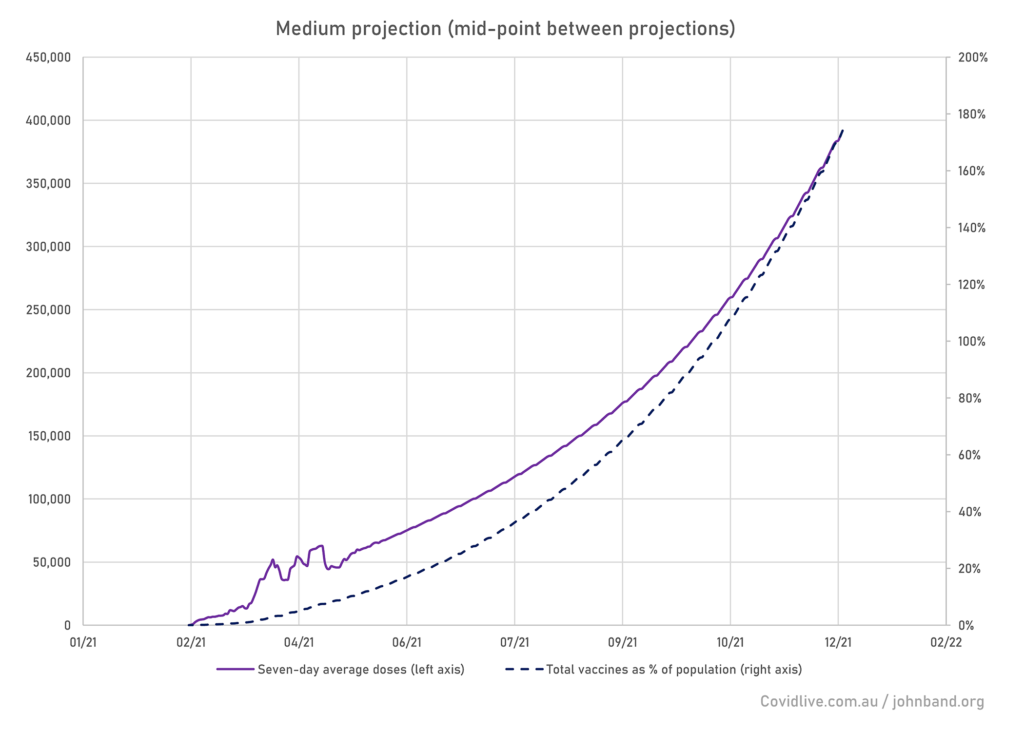

So what’s going to happen between now and the end of the year? I’ve modelled two possible scenarios based on May’s data. In the first, vaccine admistration scales up at the same linear rate (ie “governments can add the capacity to supply about 5000 new doses per week”). In the second, it scales up at the same proportional rate (ie “governments improve capacity by about 7% per week”):

Which of these vaccine scenarios is more likely?

Well, we know that global vaccine supply will grow exponentially as production techniques improve and new facilities come online. Australia is under contract to receive 40 million Pfizer doses and 10 million Moderna doses during 2021, which would together account for 194% of the population. Since about 6% of the population have already had AstraZeneca, this would achieve the 200% target. That holds even if every remaining Australian over 50 refuses to take AstraZeneca and Novavax never reaches the market.

Building vaccine hubs is a mostly linear process. You don’t save all that much time or effort by having built one previously. But GPs should be ready to grow their dose administration in line with the growth in supply. Finally, vaccine hesitancy is almost impossible to model, but we know that a significant percentage of over-50s are concerned about AZ but not Pfizer, so the scale-up in imported mRNA doses should solve a major part of that problem.

So probably the best scenario is somewhere in the middle. Behold, the official Banditry Projection For Australian Vaccination:

Where does that get us?

Under this scenario, we reach current UK levels of immunity by August, getting the risk of deaths from a new outbreak to near zero. We’d then reach current Israeli levels of immunity by October 2021.

At this point we could safely reduce our restrictions on overseas travel to set up bubbles with other low-risk nations. Vaccination will mean that there are more of these – potentially adding much of the EU to Singapore and Hong Kong. It would also allow monitored home quarantine rather than hotel quarantine for medium-risk nations (places where vaccination hasn’t yet kept a lid on covid but there are few variants of concern and overall prevalence is relatively low). This would save places in managed/hotel quarantine for travellers from places with very high positivity rates.

By Christmas 2021 under this scenario, we’d have 90% of the population fully vaccinated. That would be more than enough for herd immunity. Hence, it should allow a return to more-or-less open borders. This would probably feature restrictions on countries that continue to have severe outbreaks and low vaccine levels, or vaccine-resistant variants of concern (if any of these ever actually show up, which they haven’t yet).

Public opinion and hence political pressure will be depressingly conservative about reducing restrictions, even after a succesful vaccine program. But taking that into consideration, at least the medium risk October model should be feasible once we’ve reached herd immunity. There may be some hope, after all.

Cover image: US Army Spc. Angel Laureano holds a vial of the Pfizer/BioNTech COVID-19 vaccine. US Department of Defense / public domain

Thank you for your optimistic take on the data. If only we could get government and media to stop focussing on the negative which is getting really tiring.

Wow, it’s nice to read a positive post about this whole covid situation. I like your style.